Explaining Federal Crime Control Policy with Punctuated Equilibrium Theory

Introduction

Historically, efforts to reduce crime have been regarded as the responsibility of state and local governments. The late-1960s saw a dramatic shift in this attitude with the passage of the 1968 Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act. Not only did the Omnibus Act mark federal entry into crime control policy, but it also resulted in a significant shift in the use of federal money for state and local crime control efforts. Federal criminal justice assistance funds to state and local governments swelled from nonexistent to millions of dollars by the mid-1970s.

If crime rates could explain the observed increase in federal crime legislation and spending, then one would expect continued elevated levels for both throughout the remainder of the 20th century. By 1980, the violent crime rate in the United States had risen by over 250%, peaking in 1991 at nearly 400% of its 1960 level. However, federal monetary assistance did not remain at elevated levels immediately following the 1970s – there was no significant increase until 1994. What helps explain this short, punctuated increase in federal attention to crime control from the mid-1960s through the mid-1970s? Further, what can explain other short, punctuated increases in federal attention to crime control, even after violent crime decreased to historically low levels from the mid-1990s forward?

In this post, I suggest Punctuated Equilibrium Theory (PET) may hold some answers to the questions posed above. I first outline the central tenants of PET. I then conduct a condensed analysis in the area of federal crime control policy using PET. I do this by examining federal crime control legislation data and federal criminal justice assistance funding data from the Comparative Agendas Project.

Punctuated Equilibrium Theory

As described by Baumgartner et al., “[PET] seeks to explain a simple observation: although generally marked by stability and incrementalism, political processes occasionally produce large-scale departures from the past.” That is, PET recognizes that national political systems are conservative by nature and favor the status quo. Separation of powers and other policymaking institutional rules and norms all but guarantee slow, incremental policy change unless inertial forces overpower this bias toward the status quo. The irony of this policymaking process, however, is that when enough pressure develops to overcome resistance, policy change occurs in lurches or ‘punctuations.’ Policy punctuations can be precipitated by a sudden, powerful event that cannot be ignored, or by relatively minor events that accumulate over longer periods.

The above process is driven by the fact that human cognition only allows for serial processing, rather than parallel processing. Much like humans, political systems, such as Congress and the Presidency, cannot simultaneously consider all of the issues that present themselves. Thus, policy subsystems exist to allow the political system to engage in parallel processing. Thousands of issues can be considered simultaneously within policy subsystems that are staffed by policy experts. These closed subsystems of experts, along with limited institutional attention and accepted policy framing (i.e., crime control as a ‘local’ problem), maintain stability in the system, characterized by incremental change. In PET, this is referred to as ‘negative feedback.’ However, issues cannot reside within policy subsystems forever. ‘Positive feedback’ ensues when an attention-demanding event occurs (or enough minor events accumulate over a more extended period), an issue receives increased attention from multiple venues, and people/groups outside of the subsystem mobilize. When this positive feedback occurs, macropolitical forces (i.e., Congress and/or the Presidency) intervene, and their influence creates non-incremental, punctuated policy change. Indeed, as Baumgartner et al. state, “Macropolitics is the politics of punctuation.”

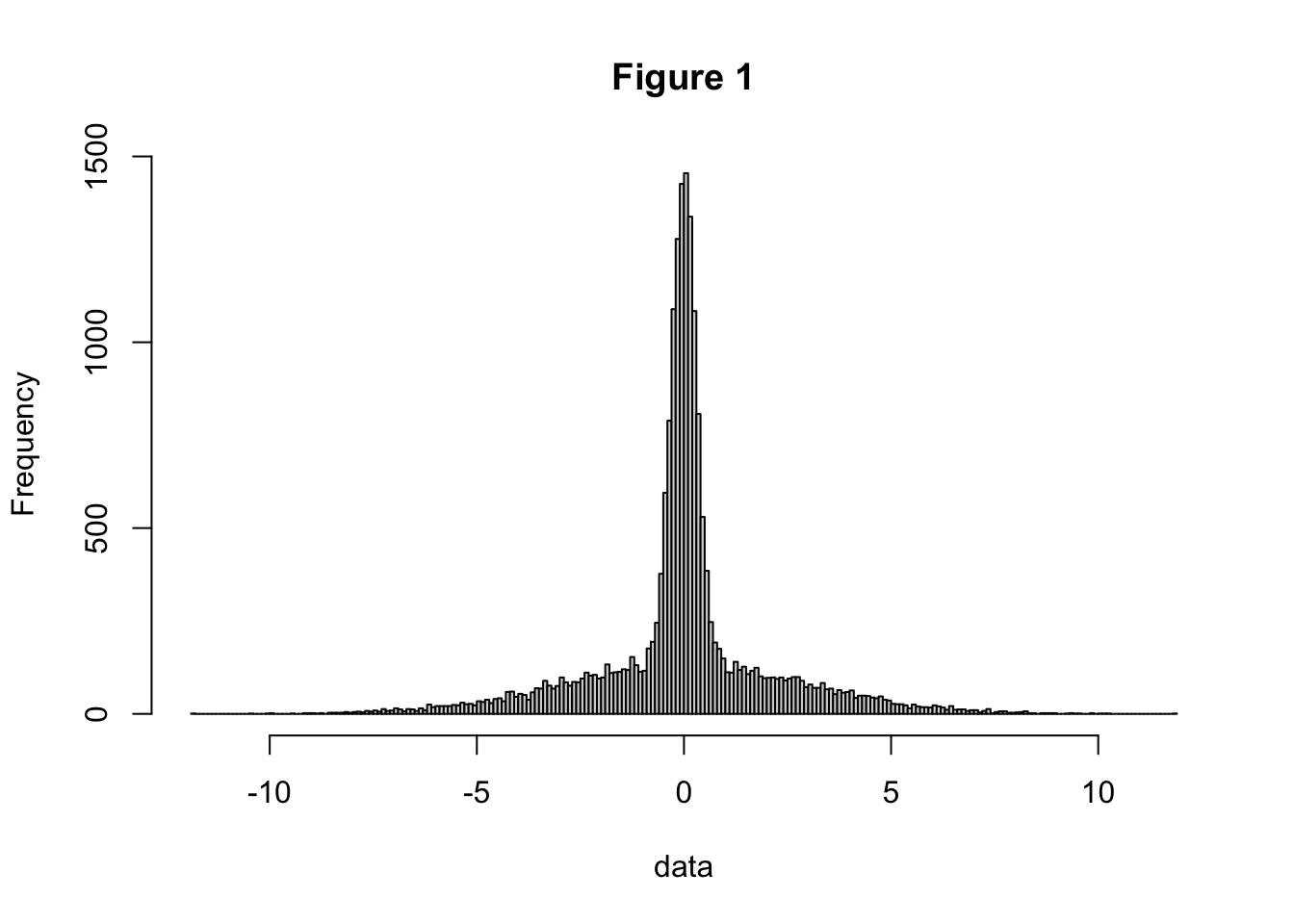

While scholars have had much success in finding the above described punctuated policy changes in various settings (e.g., incarceration rates, election results, legislative actions, environmental policy, education, etc.), the dominant testing ground for PET has been in the field of public budgeting. Baumgartner et al. provide several examples of the PET phenomenon in public budgeting. These analyses indicate leptokurtic distributions, similar to the distribution generated below (Figure 1).

In leptokurtic distributions, there are a great number of small changes centering around zero. But there are also long tails, indicating that radical departures do occur, albeit with much less frequency. This distribution is consistent with PET. While the central peak of change is centered around zero, and minor, incremental policy changes are what are typically experienced, there are much more abrupt and radical policy changes lurking in the tails of the distribution that, while occurring much less often, do transpire.

PET and Federal Crime Control Policy

As stated previously, historically, crime control has been regarded as the responsibility of state and local governments. Federal efforts have rarely been a means of crime control in the United States. The late-1960s saw a dramatic shift in this attitude with passage of the 1968 Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act. Interestingly, it is often believed that the federal government’s entry into crime control policy was unprecipitated, based only upon the staggering increase in crime experienced in the United States in the 1960s. Indeed, there was marked civil unrest in many cities, along with an alarming escalation in the country’s violent crime rate.

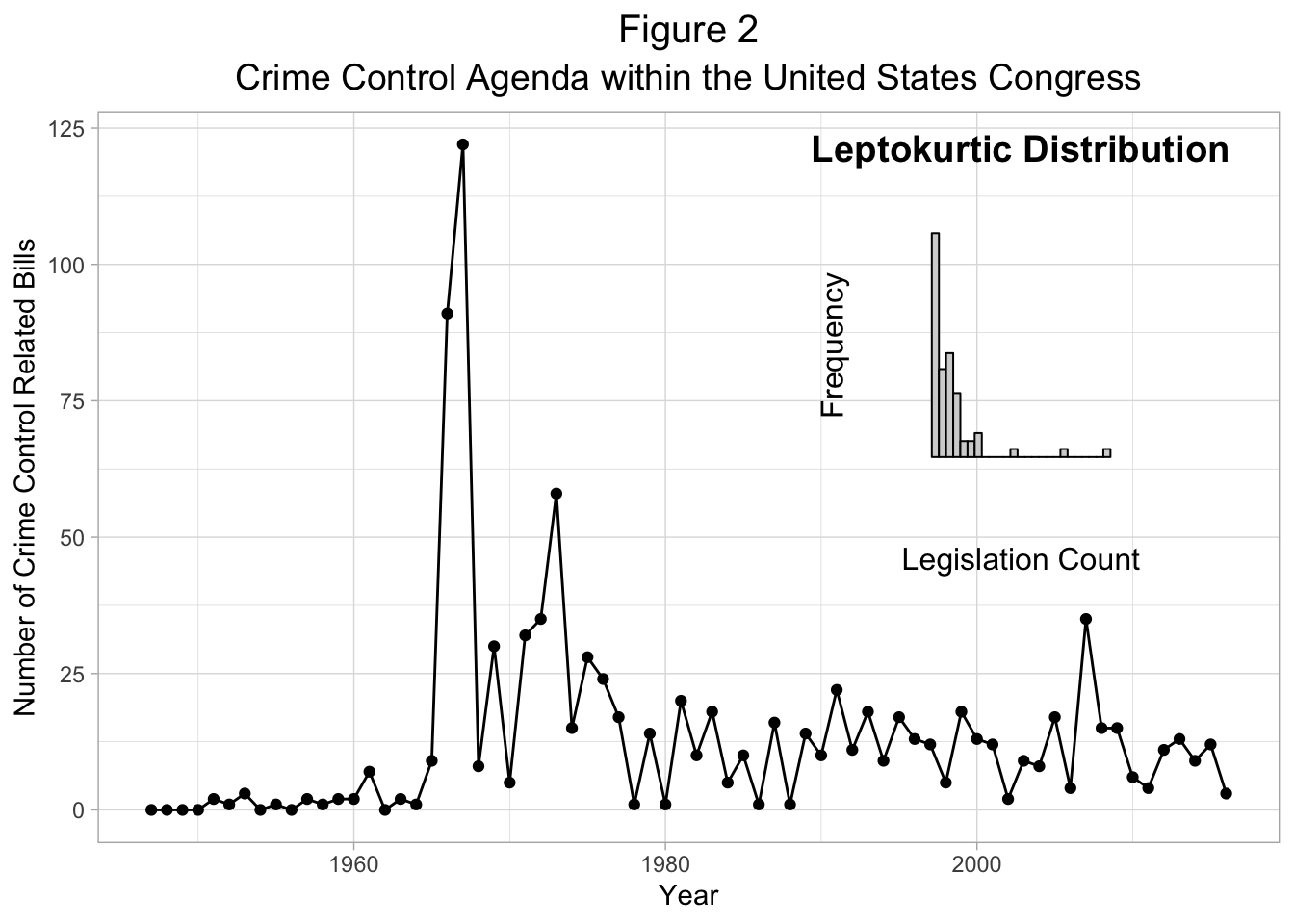

Yet, the political pressures for addressing the public policy problem of crime had been building for some time. Crime in the United States increased every year from the mid-1950s onwards, which attracted commentary in the media. However, the problem was often played down by politicians and crime policy experts. Furthermore, the issue of crime continued to be framed as a ‘local’ problem. Despite this ‘negative feedback,’ several factors finally pushed the issue of crime onto the macropolitical policy agenda. Press coverage of crime stories increased, the proportion of Americans reporting that crime was the most important problem facing the nation increased, and major urban disorders and riots swept across many American cities. Moreover, Richard Nixon began successfully framing the crime problem during his presidential campaign as a ‘war on drugs,’ calling for increased federal intervention. As a result, congressional hearings were held on crime and justice, elevating the subject of crime to the macropolitical agenda. In other words, stasis was the norm for federal crime policy before the 1968 Omnibus Act. This stasis, and the punctuation of the late 1960s federal crime legislation, can clearly be seen when plotting federal bills addressing crime control (Figure 2).

Leading up to the late 1960s there is a clear status quo of little to no proposed federal crime legislation. Following the sociopolitical circumstances described above, there is a clear punctuation in the late 1960s, followed by another lesser punctuation in the early 1970s (largely amendments to the 1968 Omnibus Act). Following the 1970s, while proposed federal crime legislation remains higher than pre-1960s levels, it returns to a fairly stable level.

To further test whether Figure 2 aligns with PET’s logic, one can examine if the distribution of federal crime legislation is leptokurtic. If PET is a plausible explanation for federal crime legislation, the distribution should reflect limited (or the absence of) occurrences of federal crime legislation, with large-scale legislative efforts lurking in the long tails of the distribution. Whether a distribution is leptokurtic or not is determined by measuring its kurtosis. Kurtosis is the average of the standardized data raised to the fourth power, with a high kurtosis measure indicating a sharper peak and longer, fatter tails (refer back to Figure 1). Typically, a distribution is considered leptokurtic when its kurtosis measure is greater than 3. The federal crime legislation distribution’s kurtosis is 18.39, thus indicating high kurtosis and a leptokurtic distribution (see Figure 2 inset).

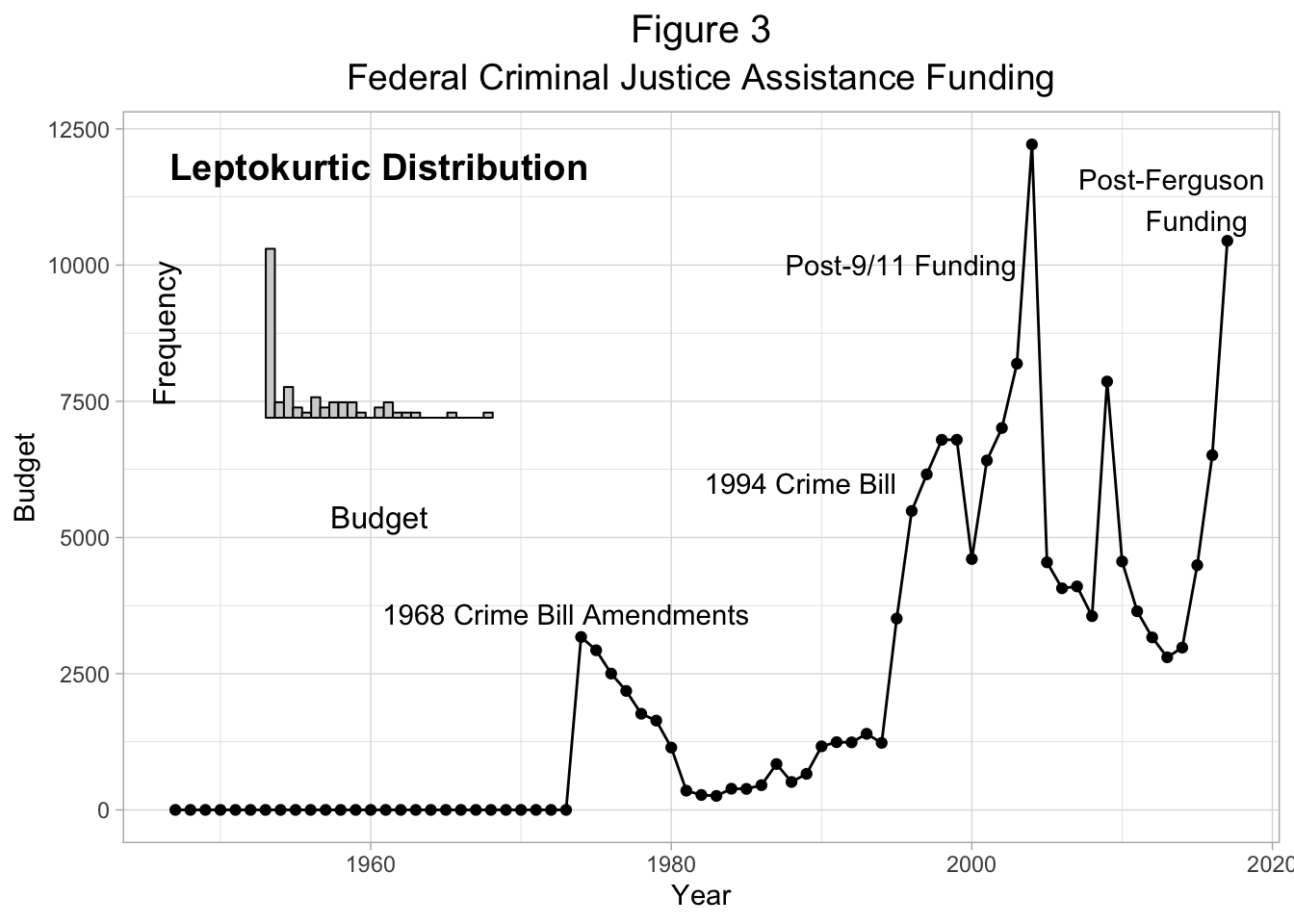

A similar punctuated pattern, along with additional punctuations, can be seen in the more-often studied public budgeting arena. Figure 3 displays the amount of federal funding dispersed to state and local governments for criminal justice assistance. One can observe stasis leading up to the punctuation of the 1968 Omnibus Act. This is followed by a stable incrementalism until the enactment of the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. The 1994 crime bill was in response to the staggering level of violent crime in the United States leading up to its passage. Recall that violent crime peaked in the United States in 1991 at nearly 400% of its 1960 level. It appears that criminal justice assistance budgeting was returning to its previous stable incrementalism following the 1994 crime bill until the punctuation of 9/11 occurred, resulting in a large increase in criminal justice assistance funding. Following 9/11, budgeting again appears to be returning to its previous stability until the punctuation of the Great Recession, which prompted the passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. This Act included large amounts of grant funding to state and local law enforcement entities. Budgeting again begins to return to its previous stability until a rise in funding occurs due to the punctuation of Ferguson Missouri in 2014, which resulted in increased funding for police reform. The kurtosis measure for the federal criminal justice assistance funding distribution is 4.44. Thus, while the distribution is not as intensely leptokurtic as the legislative distribution, it is still in line with PET (see Figure 3 inset).

In sum, while incrementalism is the norm for federal crime control policy, punctuating events, although unlikely, do occur and can result in increased macropolitical actions whether legislative (Figure 2) or budgetary (Figure 3). PET allows for these unpredictable exogenous events, which can result in ‘lurching’ policy changes.

A Look to the Future

While PET helps explain the above-listed short, punctuated increases in federal attention to crime control, it will be interesting to see what occurs following the recent ‘defund the police’ movement. The death of George Floyd on May 25th, 2020, much like the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, may be a punctuating event. While the punctuating event in Ferguson, Missouri, resulted in an increase in federal criminal justice assistance spending, one result of Floyd’s death has been a call to defund police departments across the United States. It is interesting to note the difference in framing between these two events. After the death of Michael Brown, the framing was primarily ‘communities need improved policing.’ This frame was underscored by President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing the following year, which included enhanced federal funding support for sub-federal law enforcement agencies.

In contrast, in the months following the death of George Floyd, the framing of police-related policy has often been ‘communities need less policing’ (i.e., defund the police). Will the punctuating event of George Floyd’s death result in increased spending for police reform as the events in Ferguson Missouri did? Or will the opposite, with a different framing, occur: a decrease in federal criminal justice assistance funding (i.e., defunding)? Only time will provide the answer to these questions, but the answers will pose an interesting interrogation of PET.