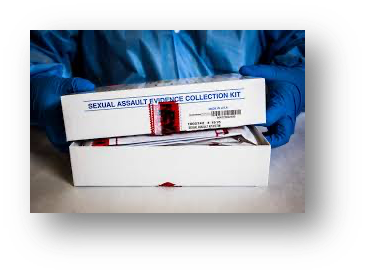

Evaluation of a Jurisdiction's Mandatory Sexual Assault Kit Testing Policy

In 2014, a jurisdiction’s police department came under public criticism regarding past non-testing of sexual assault kits (SAKs) for sexual assault investigations. From 2004 through 2013, approximately 77% of all SAKs received by this jurisdiction were never submitted to a crime laboratory for processing. As a result, a city ordinance was passed, requiring, in part, that all SAKs received by the jurisdiction’s police department be submitted to a crime laboratory for analysis within 30 days of receipt. The policy was implemented on November 1, 2014 and was effective immediately. This sharp implementation allowed us to leverage the power of a natural experiment to analyze trends during the pre- and post-implementation periods and observe what effect, if any, the mandatory SAK testing policy had on arrest rates for sexual assault with the jurisdiction.

We used a Bayesian structural time-series model (BSTS) to estimate the causal effect of the mandatory SAK testing policy. BSTS models infer causal impact by predicting the counterfactual treatment response in a synthetic control that would have occurred if no intervention had taken place. That is, a statistical model of what we would expect the arrest rate to be if the mandatory testing policy had not been implemented is estimated. Deviation from this expected value is then calculated.

The enactment of the mandatory SAK testing policy was associated with a a 16% relative decrease in the arrest rate for sexual assault after implementation of the mandatory Code-R kit testing policy. The probability of the policy implementation causing the observed decrease was estimated to be .66. Accordingly, the most conservative interpretation of the results is that the policy implementation did not have an effect on sexual assault arrest rates. However, there is a better-than-chance probability that the implementation caused the 16% decrease.

While an increase in DNA profiles in CODIS from additional SAK testing will likely assist in the identification of serial rapists (the studied jurisdiction has already seen some success in this area), it appears, based on the available data, that testing of all SAKs will not provide the additional evidence needed, on average, to increase accountability for sexual assault offenders within the studied jurisdiction. SAK testing policies are a necessary component of sexual assault investigations, but as our results show, mandating SAK testing is not sufficient on its own. Paralleling other research, it was found that the state crime lab was logistically overwhelmed by the increase in SAK submissions, with wait times for DNA results from the state crime lab almost doubling (18-24 months) upon policy implementation. Further, increased standards required in sexual assault investigations can logistically overload investigative staff. It should be noted that the studied jurisdiction significantly increased staffing levels in the Special Victims Unit during the post-implementation period. The observed downward trend may have been amplified even further if this staffing increase had not occurred.

Above is a link to the white paper that resulted from this policy evaluation. A full research manuscript for the study is currently under peer-review.