Policing in a Pandemic: How Pracademics and Data can Help

This blog post was originally posted on the website for the Police Practice & Research journal and can be viewed here.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a public health emergency that has drawn on for an extended period. The pandemic has infected tens of millions and killed over one million people worldwide. Police agencies have been asked to take on non-traditional roles during the pandemic: encouraging/enforcing social distancing restrictions, encouraging/enforcing mask mandates, enforcing stay-at-home orders, assisting in coordination of government’s overall response to the pandemic, all while continuing ‘typical’ policing mandates. There is no shortage of debate on whether police agencies should be enforcing social distancing, mask-wearing, or stay-at-home orders. This blog sidesteps that debate by focusing on police agencies’ internal strategies to the COVID-19 pandemic. That is, what should police agencies do to protect their employees?

The following report outlines the successful strategy of using pracademics for managing the internal response to the COVID-19 pandemic (the pandemic) in one capital city police agency. The success of pracademics in the area of pandemic response perhaps should not be surprising. As has been emphasized in Police Practice and Research and elsewhere, pracademics can evaluate complex research and synthesize its findings to create policy; and, perhaps even more importantly, understand the culture within a police organization and “convince, cajole, and guide an organization” to better implement relevant evidence-based strategies. As outlined by Kalyal, Huey, Blaskovitz, and Bennell, policy implementation within police agencies often fails due to lack of domain knowledge in a particular area. Police leaders value data to assist in their decision-making, yet there is often a lack of data literacy within police agencies. Pracademics can provide this data literacy to police leaders. In this particular circumstance, the evaluation and dissemination of consistent and timely data were instrumental in informing the agency’s leadership of the pandemic-related state-of-affairs within the department, and convincing leaders to provide additional resources to tackle the problem.

Pracademics

At the examined agency, two pracademics were tapped as a resource for the agency’s internal pandemic response. One of the pracademics is a detective within the agency who holds a PhD in Health Education with an emphasis in Emergency Medical Services (P1). He has a working and teaching relationship with the local university and its medical center. Because of this relationship, he regularly consumes the most up-to-date literature on COVID-19, as well as consults with epidemiologists. He was able to synthesize this knowledge and information into procedures that were practical for a police agency.

The other pracademic is a Captain within the agency who is a PhD student in Political Science with an emphasis in Public Policy and Public Administration, as well as a NIJ LEADS Scholar (P2). He regularly conducts research on policing and has relationships with policing academics. He regularly keeps abreast of policing-related pandemic research and leverages that research to promulgate agency-specific policy and procedures.

Initial Pandemic Experience

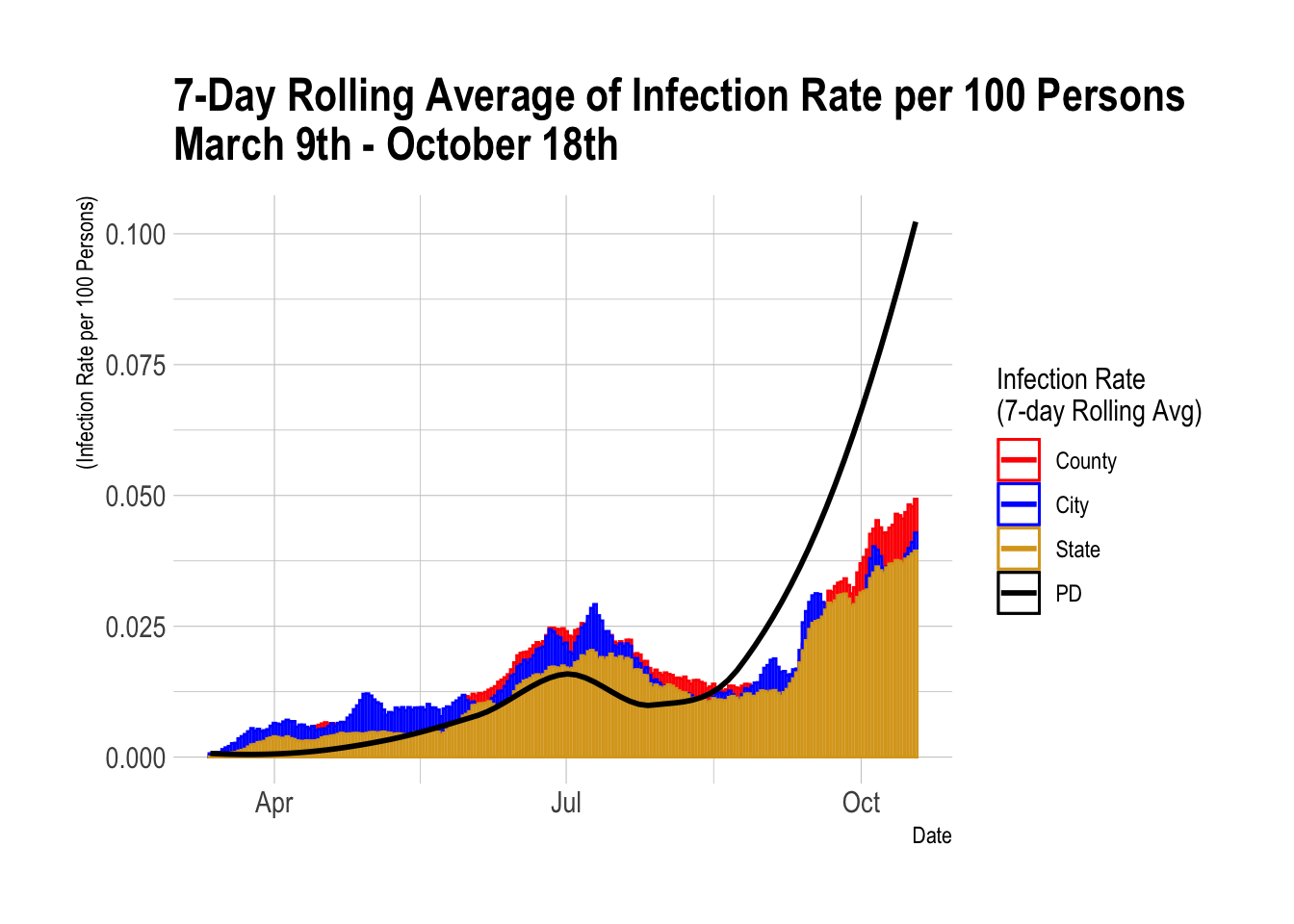

At the beginning of the pandemic, P1 was the sole individual in charge of the agency’s internal pandemic response. He was identified for the role due to his education. The state where the agency is located did not have an extremely severe ‘first wave’ of the pandemic. As shown in the plot below, the agency was able to keep its internal infection rate below city, county, and state levels. Early on (March through May), this was largely accomplished by fairly good policy compliance with officers wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) and moving all non-patrol-based personnel to work-from-home status. Additionally, a robust quarantine system was enacted, as follows:

- Upon a significant exposure, an officer is quarantined during the identified COVID-19 incubation period. Once the time-frame for incubation passes, the officer is required to get a COVID-19 test at the local university medical center. If the officer tests negative, they return to work.

- A significant exposure includes less-than-momentary physical contact with a COVID-19 positive individual, or close contact with a COVID-19 positive individual while the officer is not wearing PPE.

- Upon becoming symptomatic, an officer is quarantined and required to get tested at the local university medical center. If the officer tests negative, the quarantine is lifted.

- If an officer tests positive, they are quarantined for 14 days and return to work after receiving a negative test result.

Despite the above, the agency experienced an increased rate of infection during the months of protests and riots following George Floyd’s death at the end of May. However, this increase largely mirrored the increase in the surrounding communities and thus, at the time, did not appear specific to the police agency. As a result (along with exhaustion among the agency’s personnel), PPE compliance was largely reduced, and non-patrol-based personnel returned to work. Further, P1, out of necessity, focused most of his attention on his operational responsibilities dealing with no less than 200 protests during this period.

Then, around the beginning of September, as mitigation strategies were rolled back and less emphasis was placed on the internal pandemic response, the department saw a significant surge in its internal infection rate. As the agency experienced this surge, the Chief began to place a renewed emphasis on the agency’s pandemic response. In addition to P1, the Chief appointed a command-level employee to put ‘weight’ behind the promulgated policies. P2 was identified for the role due, in part, to his educational background. He began working with P1 on October 18th, 2020.

The plot below visualizes the agency’s above-described experience with the pandemic from March through October 18th, 2020.

As seen above, beginning in September, the agency’s infection rate per 100 persons was worryingly higher than the surrounding city, county, and state infection rates.

Data-Driven Response

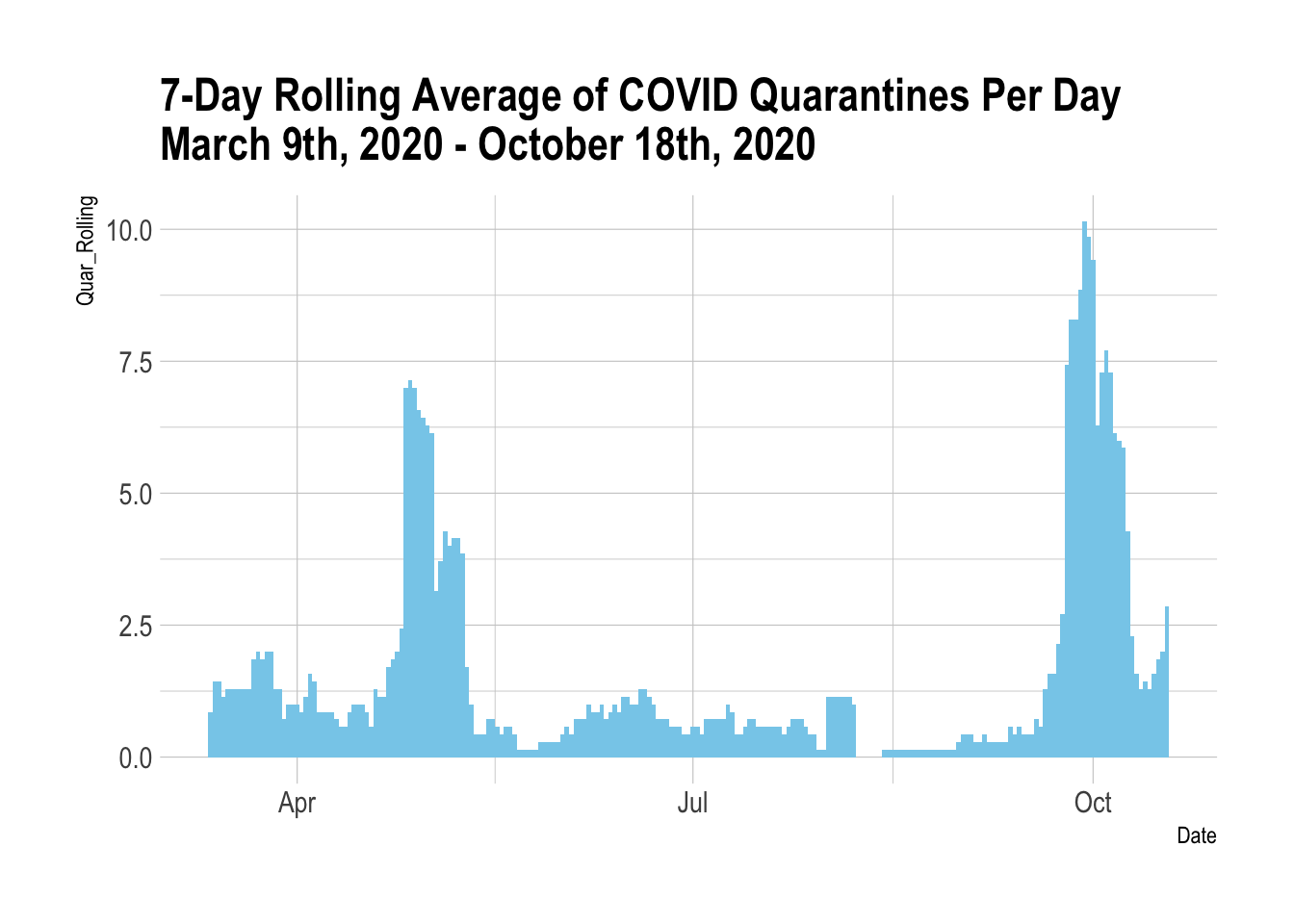

The first action taken by P1 and P2 was to examine the available data. This was accomplished with a spreadsheet P1 had been keeping of all positive cases and quarantines since March. Similar to the plot above for positive cases, plots for quarantines were also generated (similar to the plot below).

Keep in mind, the above chart is for the seven-day rolling average of quarantines per day. That is, by October, the agency was placing approximately ten additional officers on quarantine every day. These quarantines could last up to fourteen days. At its peak, the agency had approximately 40 officers on quarantine at once. Functionally, this means quarantined officers equated to approximately 7% of the agency’s entire sworn staff.

The impact of P1 and P2’s ability to analyze and convey this data to the command staff can not be understated. Updated plots were generated and discussed weekly in command staff meetings. Further, these data and translation of them were placed on the agency’s internal “COVID dashboard” weekly. The ability to analyze data and effectively translate their meaning resulted in the following:

- Across the board compliance with PPE requirements

- Return to work-at-home status for non-patrol-based personnel

- Acquisition of quick-result antigen tests

- Hiring of a contract EMT to assist in the pandemic team’s internal testing regime

- All recruits and training staff at the agency’s academy began being tested at the beginning of every week

- Testing of other personnel began being conducted on a rotating basis

Outcome

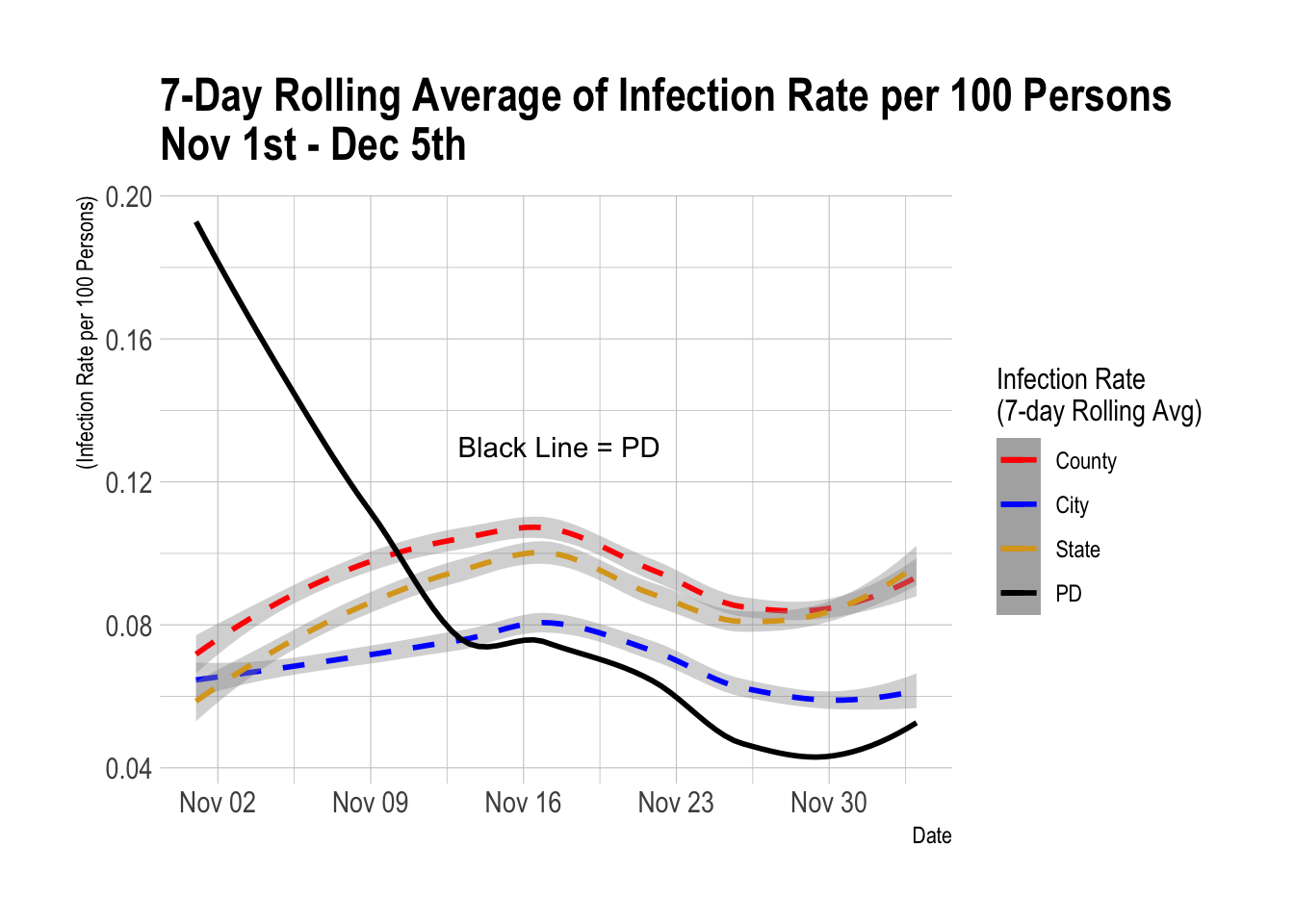

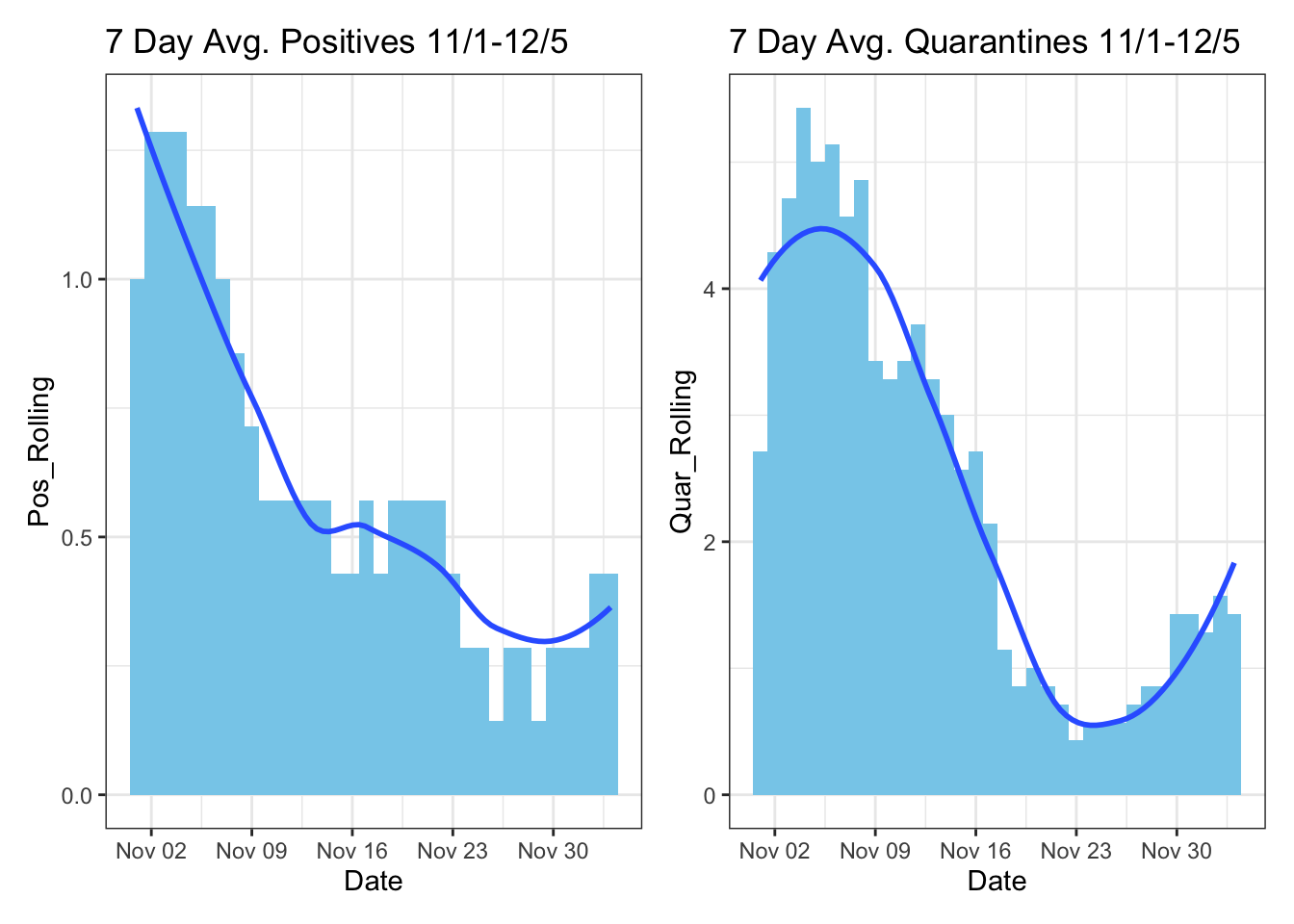

Based on the above data-driven response, P1 and P2’s ability to convey the data to the executive staff and the department at-large in a culturally informed manner, and quickly incorporating the most up-to-date academic research findings, the agency was able to drive its infection rate below city, county, and state levels. Further, quarantines were dramatically reduced, having a significant positive impact on the agency’s ability to remain staffed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the ability of pracademics to work with academics, digest research, and analyze and explain data was vital in reducing COVID-19 spread within the examined agency. By synthesizing medical and policing research, along with the practical and cultural aspects of working within a police agency, immense dividends were realized in this particular circumstance. The experience documented here is only one success story of marrying academic research and police management. There are other stories to tell, and many more to create.